PhD Student Issy Staniaszek explores the relationship between emotions and the stomach in understandings of health and wellbeing, past and present.

‘By what manual agency I wrote the subjoined pages no one has a right to inquire,’ opens the preface to Memoirs of a Stomach, Written by Himself, That All Who Eat May Read (1853).[1] Claiming on the title page to have been written by the stomach himself, and edited by ‘a minister of the interior’ (pun definitely intended), the book was in fact written by Sydney Whiting, a London lawyer and struggling poet. It was extremely successful commercially, running through at least seven editions and being translated into French in 1888.[2]

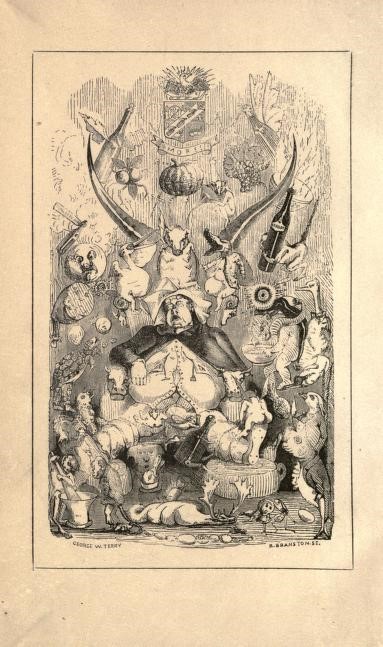

The stomach takes the reader on a journey through the incidents of his life, commenting on the ways that his owner’s actions and diet have affected him, and the ways that he has affected the life of his owner. Intended to be humorous, yet concluded with an earnest list of ‘rules for special practice in the court of health’, the Memoirs frequently and earnestly remind readers to take care what they feed their stomachs, for the organ is more sensitive and powerful than they may have thought.[3]

The Memoirs are a somewhat late example of the popular eighteenth-century genre of the ‘it-narrative’, which saw the ideals of sensibility and sentiment applied to animals and inanimate objects.[4] The stomach certainly embodies tropes of sensibility: his ‘delicate temperament’ is listed alongside his ‘humour, his satire, and his philosophy’ in the editor’s preface.[5] In a humorous episode in which he makes known his displeasure at being deprived of his dinner because his owner is too busy wooing a woman, the stomach proclaims, ‘my advice to every lover… is, take care of your Stomach, for his influence is greater than you imagine’.[6] He goes on:

The ancients were wrong, when they attributed to [the liver] the seat of the affections; and the moderns are equally so in debiting love to the account of the heart. The stomach is the real source of that sublime passion, and I swell with pride and inward satisfaction when I make the avowal.[7]

This proclamation of the importance of the stomach as a seat of emotion, combined with the stomach’s opening claim that ‘as far as intellectual faculties are concerned, I consider I hold a superior position to my helpmate Mr. Brain, for while I reside in the drawing-room floor, he lives in the attics’, shows the primacy of the stomach in Victorian conceptions of the body.[8]

The nineteenth-century public were certainly preoccupied with concerns for their stomachs. Charles Darwin famously filled his letters with details of his ailments, medically-authored books such as the inflammatorily-titled Demon of Dyspepsia (1888) were bestsellers,[9] and the frequency with which characters in nineteenth-century novels suffer with stomach ailments has been remarked upon: Emilie Taylor-Brown lists occurrences in Dickens, Byron and Bulwer-Lytton, to name but a few.

While ideas of the stomach as a seat of amorous passion may seem alien to us today, as Ian Miller notes in his book A Modern History of the Stomach (2011), the fact that we still use phrases such as ‘I can’t stomach bragging’ or ‘I have no stomach for arguments’ implies that we still conceive of the stomach in something more than a purely medical sense. As Miller notes, ‘its association with temper and pride implies that the organ was once imbued with emotional characteristics, a phenomenon not easily accounted for in strictly scientifically defined terminology’.[10]

When I first came across Memoirs of a Stomach, I laughingly flicked through it as an amusing example of Victorian ephemera. However, I soon began noticing that the connection between gut and emotion is still being made in our own health-obsessed culture. Activia’s 2015 Happy Tummies Movement encouraged people to share their #happytummy stories on social media in order to win hampers of fibre-filled yoghurt, as well as having social media influencers share advice for maintaining a ‘happy tummy’ that don’t sound a million miles away from Mr. Stomach’s advice from 1853. And Elle magazine have proclaimed gut health to be this year’s latest ‘wellness trend’, featuring interviews with the owner of a bakery called ‘The Happy Tummy Co’ alongside a neuroscientist who claims that a healthy gut is the key to controlling our emotions.

Perhaps Mr. Stomach’s claims will be proven to have truth in them? While yoghurt companies and other peddlers of ‘probiotics’ have been claiming this link for years, only recently has more funding been granted for public research into the so-called ‘gut-brain connection’. Meanwhile, Memoirs has found a slightly bizarre new lease of life: in 2014 food artists Bompass & Parr produced a facsimile edition of Memoirs of a Stomach accompanied by images of the insides of celebrity chef Gizzi Erskine, taken with a pill camera. This somewhat gruesome creation was lauded by critic Nicola Twilley for the New Yorker for showing that ‘the Victorian interest in digestion was accompanied by quite an accurate intuition regarding its mechanics’. Personally, I feel that the public event in which Erskine swallowed the pill live on stage smacks of a stunt more than a scientific endeavour, and only serves to further illustrate the ways in which our connection to our bodies is something more emotionally charged than simply clinical.

[1] Memoirs of a Stomach, Written By Himself, That All Who Eat May Read, 4th ed. (London: W.E. Painter, 1875), p.vii. https://archive.org/details/memoirsofstomach00whitiala

[2] Joyce L. Huff, ‘The Narrating Stomach: Appetite, Authority and Agency in Sydney Whiting’s 1853 Memoirs of a Stomach’ Body Politics 3 (2015), pp.75-93. http://bodypolitics.de/de/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Heft_5_05_Huff_Narrating-Stomach_End-1.pdf , p.77.

[3] Memoirs, p. 129.

[4] Mark Blackwell, ‘The It-Narrative in Eighteenth-Century England: Animals and Objects in Circulation’, Literature Compass, vol. 1, issue 1 (2004; online version 2005) https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-4113.2004.00004.x

[5] Memoirs, p.vi.

[6] Memoirs, p.100.

[7] Memoirs, p.101.

[8] Memoirs, p.vii.

[9] Adolphus E. Bridger, The Demon of Dyspepsia, or Digestion Perfect and Imperfect (London, 1888), https://wellcomelibrary.org/item/b21519213#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=4&z=-0.9129%2C0.1014%2C2.8852%2C1.4599

[10] Ian Miller, A Modern History of the Stomach: Gastric Illness, Medicine and British Society, 1800-1950 (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2011), p.3.