I wanted to follow in any number of my mother’s footsteps but not these.

Entering the same medical center where I’d accompanied Mom to consult an oncologist felt surreal. This appointment was for me.

As an author with a spiritual bent, I’d rather try acupuncture or special diets than Western medicine. At 53, with a husband who owns an eco-friendly painting company in New Jersey, I am as “granola” as I was at the Mennonite college where we met.

But with no routine way to monitor questionable cells, and given my family history, two surgeons I consulted recommended a hysterectomy. Biopsies would tell more.

“I have so much to live for,” my mother had told her oncologist, after learning of the malignancy that would take her four months later. “75-years young,” we’d said, her curly bob still her natural chestnut brown.

Of the five Mennonite farm-girl sisters in the photo we bring out at gatherings now, cancer took three.

I made plans for after my surgery, marking down my son’s Indie rock band’s concerts. In a more realistic mood, I stock-piled novels and loaded the freezer with Trader Joes’.

My second opinion surgical oncologist had kind eyes. His fuzzy beard softened his face. He answered all my questions but one. I sat forward, wringing my hands.

“A friend wondered -- how many surgeries of this kind have you done?”

“So many I’ve lost track,” the doctor replied.

As he wheeled over on his little stool with papers to sign, he sat patiently next to me while I read our agreement. His unrushed style contrasted with my whirling mind. I’d heard that surgeons were “hired guns.” I wasn’t expecting to find a healer.

I reassured myself, “Lots of women do this.”

My surgery date: one day following the third anniversary of my mom’s death. On the way home from that appointment, I yelled several unprintable phrases. My husband took me to pick up my favorite sushi.

“It’ll be okay,” Jonathan reassured me, and I put down my ninja-sized swords so I could eat.

As I told friends and family about it, I found a secret society of women who’d had this procedure but were private about it. The Center for Disease Control estimated that a third of women will join our womb-free club by age 60.

Weeks before the procedure, I felt the same nausea I experienced the day in the hospital room when we learned that Mom had to get radiation on her brain.

I logged into apps for guided relaxation and imagined my very long life as I danced to my son’s band’s lyrics: “I just wanna play some songs before I die.” I saw a Qi healer. My husband held me tight in embraces I called “Jonathan Reiki.”

Drinking herbal tea, I visualized white light healing my body. My new mantra: “healthy, singing cells.”

Mom, I said, I know you want me to be healthy. She’d grown tomatoes and zucchini in her garden and often sent me home with foods and flowers. Jonathan and I mined the farmer’s market for the freshest zucchini, beets, and apples.

When I worried that my stress was impacting our dog, Jonathan tried to reassure me she just needed “me time” in another room.

Days of migraines followed; one made me lose my dinner. With heart flutters, I gave in to anti-anxiety pills.

“I hope after your surgery, you see more colors in the world,” my mom’s sister said, calling to wish me well. It sounded like a lofty goal.

Mom, I said, please help.

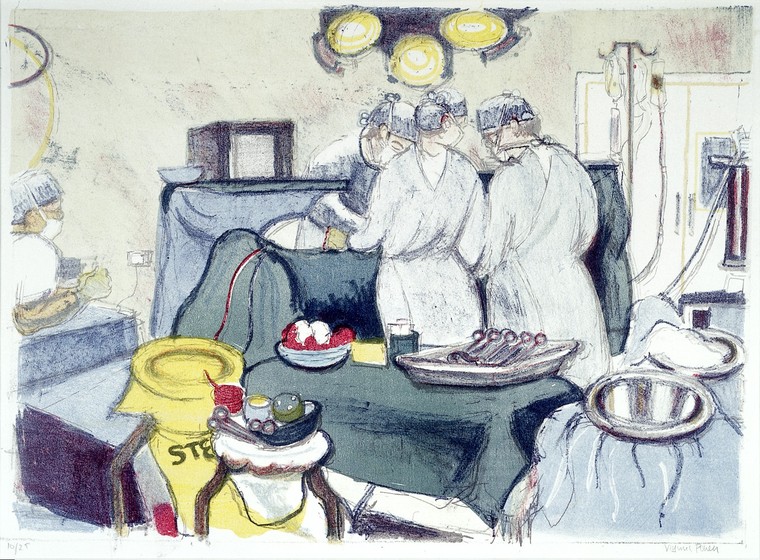

Wheeling into surgery, I pinched my eyes closed at seeing the robot in the corner.

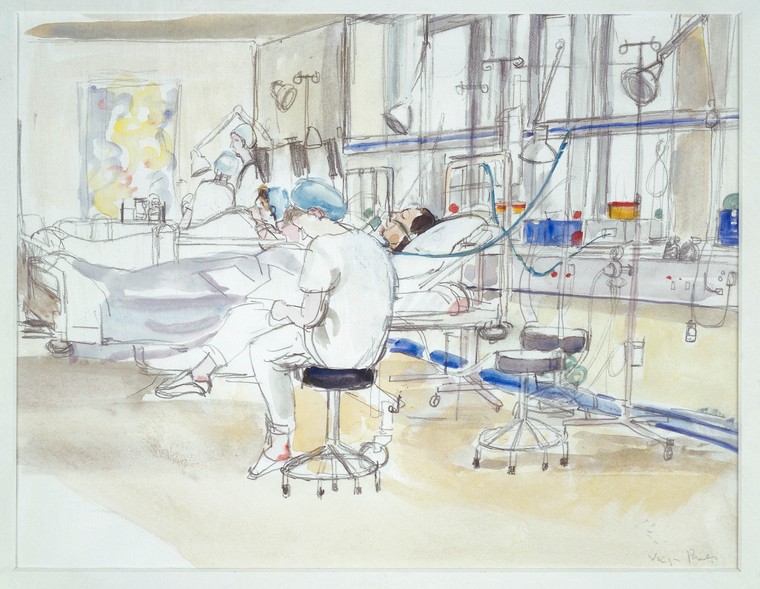

A kind nurse squeezed my hand and asked me how I was doing. When I got migraines as a kid, my mom put cool washcloths on my head and comforted me. I wished she were here.

“I’m okay,” I lied.

“Sorry my hands are cold,” the surgeon said, as he arrived to hold my right one.

This was what Mom often said as we held hands to pray before meals in my parents’ Pennsylvania home. Maybe she was close after all.

“You have to tuck her in,” the nurse teased the doctor.

I wondered if it was romantic banter, or whether I’ve watched too many hospital dramas.

All tucked in and the three of us holding hands, I said a silent prayer.

Jonathan appeared after I woke, and we caught up while I downed Percocet and vanilla pudding. He told me that my biopsy was clear.

I was eager to go home and see our son, who was watching our dog. That was when I noticed the stitched incisions. I imagined the robot poking around, seeking a wandering womb.

Jonathan raced to ask the nurse, who said this was normal for robotic surgery.

As I hobbled into the living room on Jonathan’s arm, Gabe and I joked about how light our hug needed to be. I hated feeling this frail.

The next morning, he caught me tidying up the bedroom.

“So the day after surgery, you’re cleaning up before your friends visit?” Gabe asked.

“Ridiculous, right?” I laughed, picking up another pillow before sitting down. It took me days to accept feeling so vulnerable.

My tests came back normal.

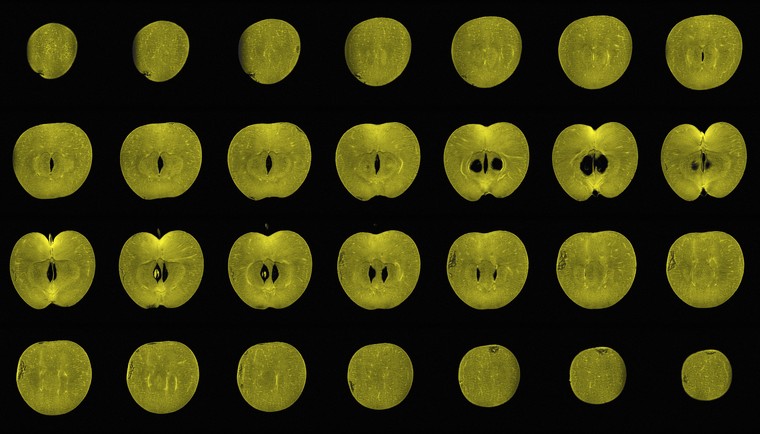

“I hope you learn to love ordinary things,” Mom wrote in a birthday card over a decade ago. I’d been a stressed-out mom, and she nudged me to stay present.

Every year, our family made applesauce in her kitchen. Mom presided over large pots, cooking Cortlands and other varieties.

“Be sure to serve yourself a bowl while its warm,” she said, making sure we didn’t miss it.

I cut a farm market apple on a wooden board below her picture on my kitchen sill. I savor its sweetness for both of us.

When I went for my follow-up, the surgeon urged me to get genetic testing. I said it might make me more anxious.

“It will give you power,” he reassured.

I don’t know how I got so lucky to have a surgeon who knows what medicine is. But I thanked him and walked straight to the genetic testing office to make my appointment.

Cynthia Yoder has written profiles of world leaders in the arts and sciences for Princeton University and Bristol-Myers Squibb as a freelance writer. With an MFA from Sarah Lawrence College, she is the author of three books, including Crazy Quilt: Pieces of a Mennonite Life, a modern memoir about a year exploring her PA Dutch Mennonite roots during a personal crisis. Her essays appear in Just Moms: Conveying Justice in an Unjust World (Barclay Press), New Jersey Monthly, Mothering, ADDitude Magazine, and her blog. Cynthia lives in New Jersey with her husband, Jonathan; their son, Gabe, recently graduated college.