The short-lived but heart-felt public performances of gratitude that characterised the first weeks of the UK coronavirus lockdown were welcomed by many healthcare workers unused to such enthusiastic acclaim.

Most surgeons, however, are no strangers to gratitude. They have a reputation for attracting effusive thanks and admiration, sometimes invoking the exasperation of other, less conspicuous members of a team that have also contributed to successful outcomes for patients. Giving and receiving thanks are emotionally charged, culturally shaped rituals that can be tricky to negotiate to everyone’s satisfaction. Here I explore some of the factors that underlie patients’ need to express gratitude, and why being receptive to gratitude should be seen as an intrinsic part of care-giving relationships – both in the care of others and in self-care.

Gratitude is more than an emotion. It is also a ritual bound up with recognition of social value. Surgery is consistently rated, by lay people and medical professionals, as being at the top of the hierarchy of medical specialties.[1] The concomitant reverence in which surgeons are held may contribute to feelings of deference that, in part, motivate performances of gratitude. It also helps that there is usually a time-limited period of engagement with the patient. Having a point of discharge – unlike, say, the open-ended nature of psychiatry or general practice – presents patients and relatives with opportune moments to enact their gratitude.

For some surgeons, the gratitude they receive is tied up with their sense of accomplishment, especially in the early parts of their careers. Henry Marsh, brain surgeon, writes in his memoir Do No Harm:

As I walked round the wards after an operating list with my assistants beside me and received my patients’ heart-felt gratitude and that of their families, I felt like a conquering general after a great battle.[2]

Although this sounds self-aggrandising, there is an art to being receptive to gratitude.

Over the years that I have been researching gratitude in healthcare, a recurring theme in conversations I’ve had with people who have good reasons to be grateful to surgeons is that their thanks are often deflected. A commonly reported reaction is a variation of ‘Don’t thank me, I’m just doing my job.’ Of course, being a surgeon is a job and patients are entitled to the care they receive without the obligation to demonstrate gratitude. Technically, it is a transaction. But, relationally, surgical interventions are anything but transactional. To have someone take on the responsibility of entering the body with the intention of alleviating suffering is to entertain an intimacy that is deeply privileged and frankly unnatural. When surgeons reject gratitude they may assume they are demonstrating humility – a quality, as Toledo-Pereya says, not typically exuded by surgeons who are ‘not trained to be humble by design’.[3]

Surgeons may see their self-effacing refusal of gratitude as a rare opportunity to counter their reputation as confident, commanding, self-assured operators. However, the opposite is almost always the case. The true sign of humility is the recognition that the patient’s need to express gratitude may be greater than the surgeon’s need to hear it. Being receptive to a patient’s thanks, no matter how unnecessary it is felt to be, could – and indeed should – be considered to be part of a duty of care.

A meta-narrative review of the literature of gratitude in healthcare that I recently undertook revealed a growing evidence base that expressing gratitude has a number of psychological benefits including having a positive impact on quality of life and reducing psychological distress.[4] Philosophers have also hypothesised that saying ‘thank you’ helps to reduce some of the feelings of obligation that attend the receiving of an unrequitable benefit. The surgeon–patient relationship intrinsically involves a huge imbalance of power. An encounter that comprises giving and receiving gratitude is a process of mutual symbolic identification – akin to a ceremony – in which both parties acknowledge that something extraordinary happened here.

As well as recognising that patients and their relatives need to extend their gratitude, surgeons perhaps also need to allow themselves to hear it. As highlighted recently, surgeons’ mental health is a matter for concern. It is estimated that a third of surgeons are prone to burnout and many also score highly on a scale for cynicism.[5] Studies of the impact of patients’ gratitude show that it is likely to have important effects on increasing job satisfaction [6] and protecting against burnout. [7][8]

It would be glib to maintain that gratitude is universally a good thing. It has a flip side in which it can be complicit in normalising distress and exacerbating power inequalities. Raymond Carver’s poem ‘What the doctor said’ reminds us that polite responses are sometimes what we resort to when we are at our most vulnerable. The poem’s narrator, on receiving a catastrophic diagnosis, responds with jocularity and then:

I jumped up and shook hands with this man who’d just given me

something no one else on earth had ever given me

I may have even thanked him habit being so strong.

‘Habit being so strong’ chimes with the experiences of some patients where a gratitude response kicks in even when it is totally unmerited. I have heard of patients whose cases have been shockingly mismanaged yet, they have effusively thanked those who were responsible. Their trauma perhaps renders them incapable of anything but an instinctive politeness response that they will later deeply regret – particularly if their words of thanks are echoed back to them in an attempt to undermine a well-founded complaint.

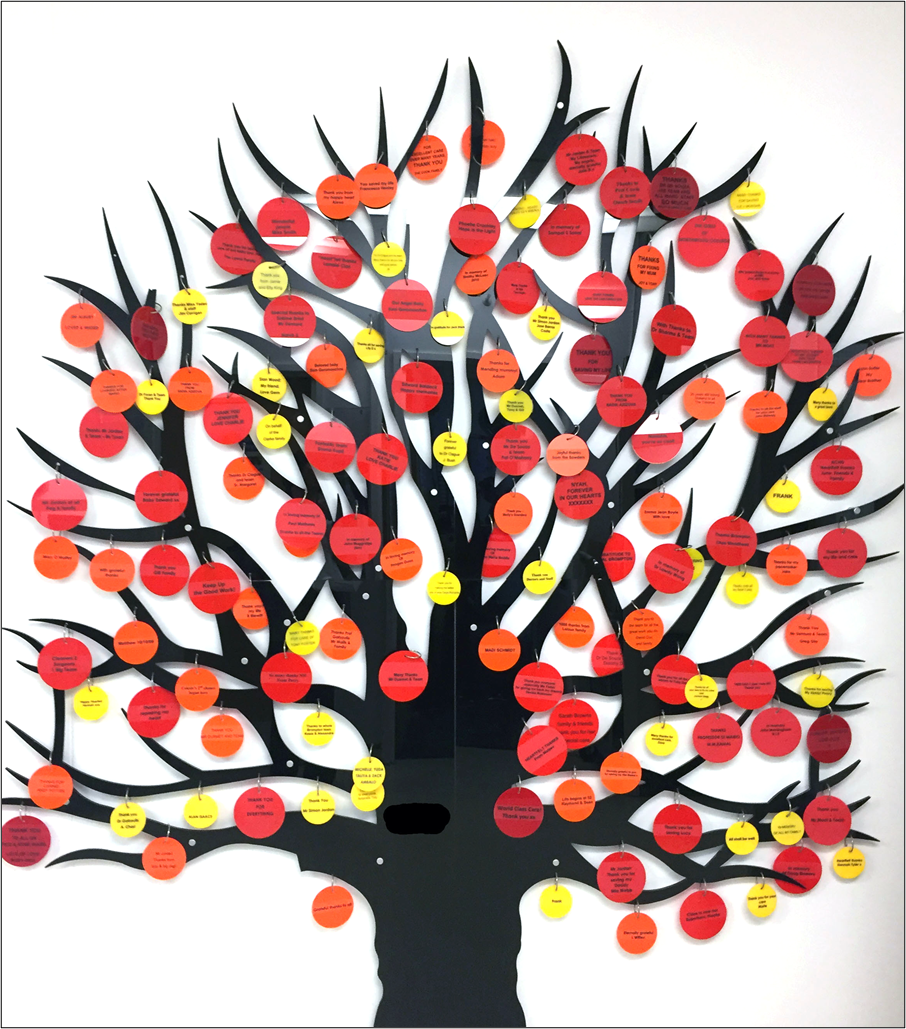

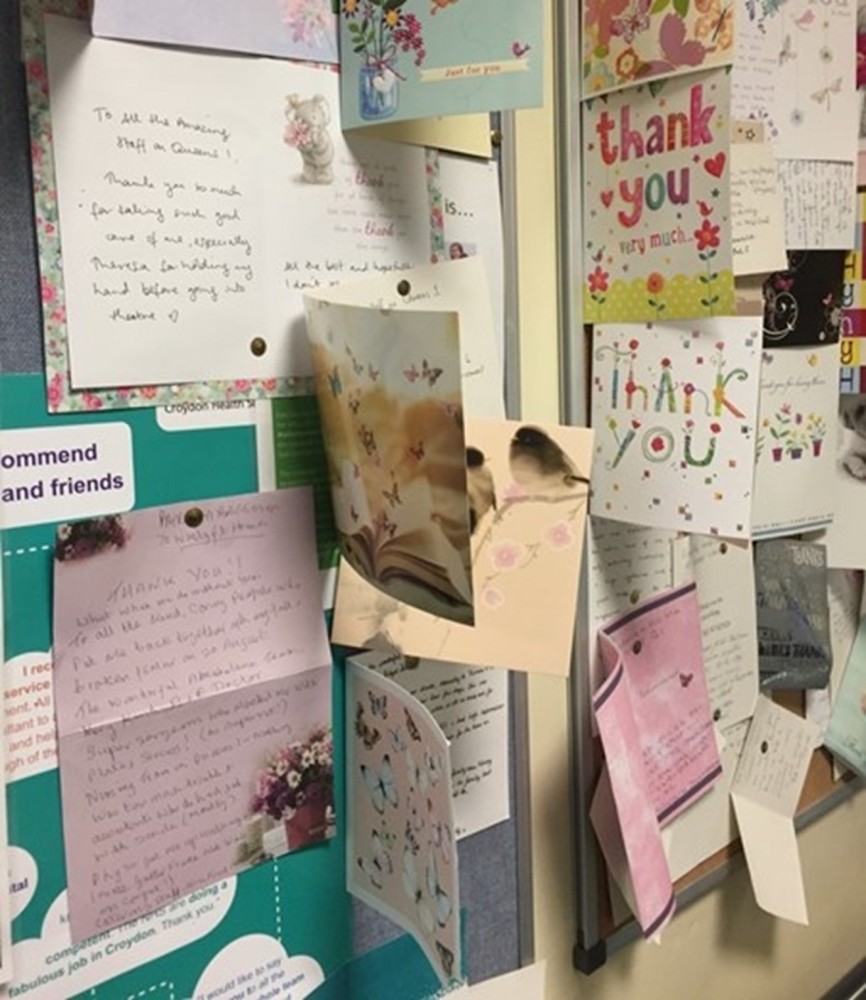

Abuses of gratitude are thankfully rare. Usually, gratitude oils the wheels of social life – we notice it more than when it is withheld than when it is bestowed. Indeed, one of the biggest contributors to workplace unhappiness is when staff feel undervalued, not by patients, but by their colleagues.[9] In this extremely challenging time, it behoves us all to recognise that gratitude is integral to a supportive culture. Small but significant moments of shared humanity are to be savoured at a time of crisis.

Giskin Day is researching the expression and reception of gratitude in healthcare as part of a Wellcome Trust-funded PhD studentship at King’s College London. She is also a Principal Teaching Fellow at Imperial College London, where she teaches medical humanities.

[1] Hindhede AL, Larsen K. Prestige Hierarchies of Diseases and Specialities in a Field Perspective. Soc Theory Heal 2019;17:213–30. doi:10.1057/s41285-018-0074-5

[2] Marsh H. Do No Harm: Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery. Weidenfeld & Nicolson 2014.

[3] Toledo-Pereyra LH. Humility. J Investig Surg 2007;20:63. doi:10.1080/08941930701234588

[4] Althaus B, Borasio GD, Bernard M. Gratitude at the End of Life: A Promising Lead for Palliative Care. J Palliat Med 2018;21:1566–72. doi:10.1089/jpm.2018.0027

[5] Upton D, Mason V, Doran B, et al. The Experience of Burnout across Different Surgical Specialties in the United Kingdom: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Surgery 2012;151:493–501. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2011.09.035

[6] Burke RJ, Ng ESW, Fiksenbaum L. Virtues, Work Satisfactions and Psychological Wellbeing among Nurses. Int J Work Heal Manag 2009;2:202–19. doi:10.1108/17538350910993403

[7] Converso D, Loera B, Viotti S, et al. Do Positive Relations with Patients Play a Protective Role for Healthcare Employees? Effects of Patients’ Gratitude and Support on Nurses’ Burnout. Front Psychol 2015;6:470. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00470

[8] Aparicio M, Centeno C, Robinson C, et al. Gratitude between Patients and Their Families and Health Professionals: A Scoping Review. J Nurs Manag 2019;27:286–300. doi:10.1111/jonm.12670

[9] Finlayson B. Counting the Smiles: Morale and Motivation in the NHS. London: King's Fund. 2002.