Last week the Surgery & Emotion project team held its first public engagement event. ‘Operating with Feeling: Pain, Art and Surgery’ was a free interactive workshop, which took place in the evening on Thursday 15th March in the Wellcome Collection’s Reading Room.

The event drew on images and objects in the collection to explore the relationship between surgery, emotion, and art over the last 250 years. In particular, we examined responses to, and representations of, pain and pain relief.

We organised the event as part of the Open Platform initiative, an event series in which content is generated by the Wellcome Collection’s audiences, allowing new voices to respond to the Reading Room’s themes. Events in this series are designed to be drop-in sessions and are advertised in-house on the day. We also used our website and social media to promote the event in advance. We were pleased to attract around fifteen to twenty participants with varying levels of knowledge of the history of surgery.

The event opened with an introduction to the Surgery & Emotion project. We then used a warm-up exercise to get participants thinking about their perceptions of surgical care, past and present. We laid out written statements about contemporary and historical surgery, asking attendees to record their first impressions. They used different coloured post-it notes to mark whether they agreed, disagreed or were unsure about each statement. This exercise was a fantastic way to promote discussion among the group about their attitudes towards and perceptions of surgery. We discussed whether surgeons should be detached from, or feel sympathy for, their patients, and whether women patients were better at enduring pain. We explored whether participants considered surgery in the nineteenth and twenty-first centuries to be a technical skill, an art form and/ or a trade.

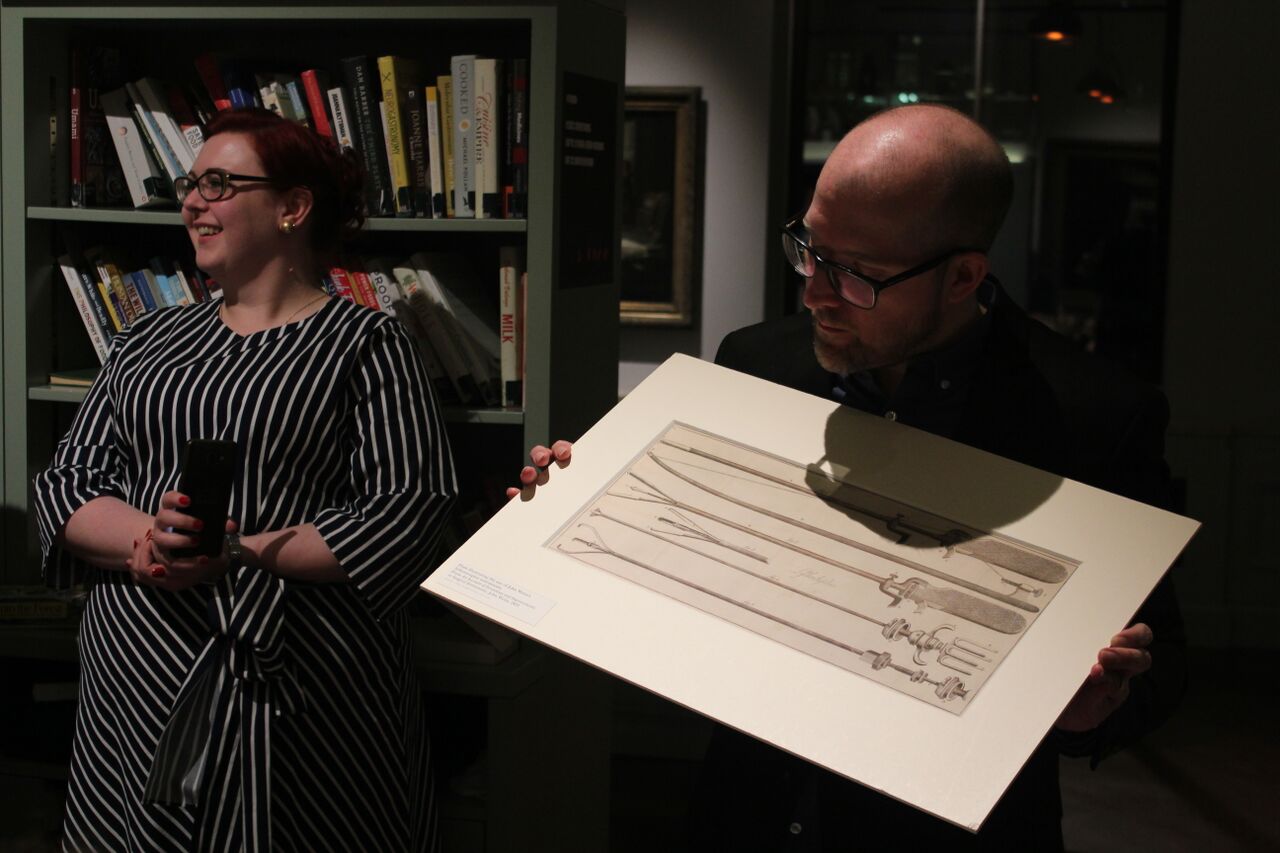

After this exercise, the project team introduced participants to different images and objects in the Reading Room’s collection, some of which are pictured here. We divided this part of the session into themes: Surgical Instruments, Dental Practices, Art and Surgery, and Quack Medicine. Participants offered their perspectives on the images and objects, while project members provided historical context and spoke about their research interests. For instance, Michael Brown (Principal Investigator) discussed lithotomy procedures and the use of forceps in childbirth. PhD Candidate Lauren Ryall-Stockton, previously Curator of the Thackray Museum, discussed public responses to historical medical instruments. Alison Moulds (Engagement Fellow) talked about dentistry’s shifting status from trade to profession and the early uses of anaesthesia in dental practice. Agnes Arnold-Forster (Research Fellow) explored cancer diagnosis and treatment in the nineteenth century, and the purpose of using art in surgical education and practice. Senior Research Fellow James Kennaway introduced attendees to some advertisements for patent medicines to highlight the commodification of pain relief.

Following this discussion of objects and artwork, we then brought the group back together to repeat the warm-up exercise. The purpose of this was for attendees to consider whether their perceptions of surgery had changed in light of the discussions that had taken place. Many participants had a newfound understanding of dentistry’s influence on surgical practice and the status of quack medicine, which they no longer regarded as the antithesis of orthodox practice. There continued to be mixed responses about whether pain relief and new technology made surgery less frightening, which reflected our discussions about the dangers of early anaesthesia and its experimental status, as well as the range of instruments used in practice.

As this was a drop-in event and designed to be informal, we did not carry out an official evaluation, but we found that participants had lots of appetite to get involved in discussion and there was a great group dynamic. We felt that the participatory ethos and the combination of exercises worked well, though covering the material within our hour-long slot was a challenge. Some attendees suggested afterwards that the event could be repeated in different contexts, perhaps in a hospital setting or with secondary school pupils. We agree that the event is very adaptable, and we’ll be thinking of ways we might re-use and develop the material in our future public engagement.