In the second of a two-part blog post, Principal Investigator Dr Michael Brown considers Robert Liston’s ambiguous reputation among his contemporaries.

In the first part of this blog post we saw that Robert Liston’s modern reputation as a speed-obsessed showman is largely the product of a mythology whose origins can be traced back to the early twentieth century. We also saw how this mythology has been uncritically recapitulated in many subsequent historical works. But all this is not to suggest that Liston was an uncomplicated figure, even in his own lifetime. On the contrary, as we shall see in this blog post, his reputation within Romantic surgery was shaped by shifting political currents.

During the 1820s, Liston’s reputation as an operative surgeon was, in his native Scotland at least, virtually unassailable. Writing to his uncle from Edinburgh on New Year’s Day, 1833, for example, the young Cumbrian surgical pupil Andrew Whelpdale claimed that, ‘We have here one of the best operators in the world Liston – A pupil of his is almost the equal, and indeed is far superior in some things to a practised surgeon of the old school’.[1] Liston’s reputation in England was, by contrast, rather more complex.

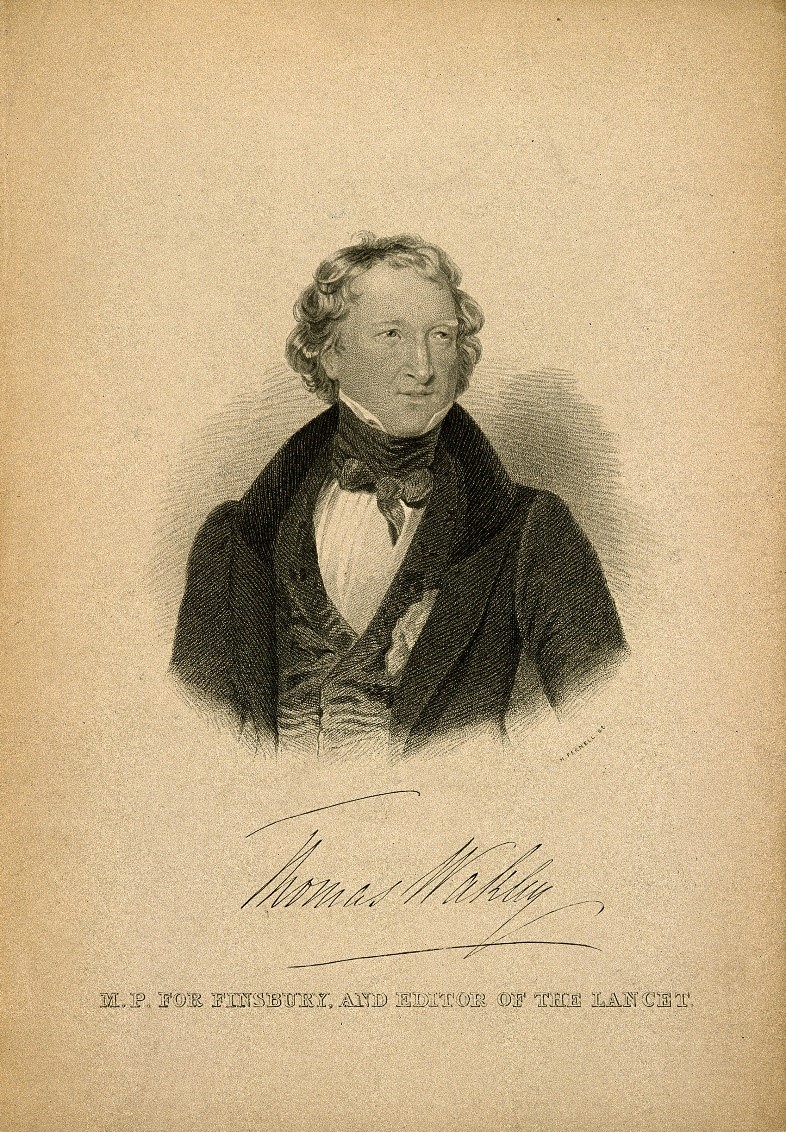

In large part this was due to the influence of perhaps the most well-read medical journal of the period, The Lancet. As I have shown elsewhere, The Lancet played a vital part in shaping early nineteenth-century surgical reputations and its attitudes were determined by the radical politics of its founder and editor, Thomas Wakley (1795-1862). However, if Wakley was distrustful of the London surgical elites, whom he called ‘Bats’ and ‘Hole and Corner’ surgeons, he was nonetheless intensely jealous of London’s reputation for surgical education and notably suspicious of Edinburgh and the ‘Celtic fringe’ in general.

Wakley was particularly enamoured of his former tutor, Astley Cooper (1768-1841), and resentful of any challenge to his reputation as the leading operative surgeon of the era, particularly if that challenge came from north of the border. Thus, one of Liston’s earliest appearances in The Lancet came in an 1823 report of an operation in which he had served as assistant to his cousin, friend and soon-to-be bitter rival, James Syme (1799-1870). This procedure, the amputation of the leg at the hip joint, was what Syme called ‘the greatest and bloodiest operation in surgery’ and had yet to be performed in Scotland.[2] Around the same time, however, it had also been performed for the first time in England by Cooper.

The Lancet’s coverage of Syme’s operation and Liston’s part in it was highly critical. Wakley was enraged by the idea that ‘the northern [i.e. Scottish] journals’ sought to use the incident ‘for the purpose of casting a shade upon the splendour of London surgery’, particularly in the way they ‘sarcastically compared the time occupied by Mr. SYMES [sic] to that occupied by Sir A. COOPER when he recently performed a similar operation at Guy’s Hospital’. Whereas Cooper ‘required twenty minutes to remove the limb’, Syme ‘according to his own account, was contented with ONE minute’.[3]

What the operation actually demonstrated, Wakley argued, was that considered judgement was superior to mere ‘manual dexterity’ (Syme’s patient died, Cooper’s did not) and he hoped that Syme would ‘never expose a patient to similar risk, nor himself to a repetition of such dreadful anxiety’. As for Liston, who, by assisting in the most physical manner, had ‘grappled with and squeezed the arteries … this circumstance is so truly ludicrous and anti-surgical, we are almost inclined to believe that the assistant operator was Mr. LISTON of Drury-lane theatre’.[4]

The reference here to the celebrated actor John Liston (c.1776-1846) highlights the ways in which The Lancet would frequently characterise Edinburgh surgery as theatrical, self-promotional and heedlessly ostentatious in contrast to the more considered and humane surgery of the metropolis. And, as Edinburgh surgery’s leading light, as well as a man whose 6’ 2” frame and physical strength shaped his identity as a surgeon, these associations stuck most closely to Liston. For example, in a quite remarkable ‘sketch’ written by ‘Scotus’ in 1830, Liston is characterised as a man ‘whose brains are obviously not contained in his cranium, but, by original conformation have been deposited, or what perhaps is more probable, have been transuded into his muscular system’.

‘Scotus’ figures Liston as a man utterly defined by his physicality and almost entirely lacking in sensibility and compassion: ‘He has brought [to the practice of surgery] a breadth of shoulder, muscularity of arm, and a merciful indifference to the tortures of the knife, seldom, if ever equalled by the coolest and most corpulent cultivators of that sanguinary art’. The question of whether this particular Liston was a good or a bad surgeon is not entirely clear. Liston’s skill reduces suffering, after all. Nonetheless, the overall perception is negative, for while ‘Mr. Liston’s merits … are of the first order of excellence’, they are ‘degraded by a mannerism bordering on buffoonery’.[5]

Such accounts were characteristic of The Lancet’s coverage of Liston during the 1820s and early 1830s. However, this was soon to change. In 1834, Liston left Edinburgh to take up a post at the North London Hospital (soon to be University College Hospital). The following year, he was also appointed Professor of Clinical Surgery at its parent institution, London University (soon to be University College London). London University was a Benthamite project, headed by the leading Scottish Whigs James Mill (1773-1836) and Henry Brougham (1778-1868). As such it drew heavily upon the rationalist traditions of Scottish medical and scientific education and consciously imported many of its leading lights from north of the border. Nonetheless, while The Lancet was often inclined to rue the institution’s overwhelming ‘Scottish influence’, they were surprisingly tight-lipped on the appointment of Liston in 1834/5.

Moreover, in 1836, Liston was the only hospital surgeon in London to attend a meeting of medical students that Wakley had organised and, from this point on, having demonstrated his radical credentials, he could, in the eyes of The Lancet at least, do no wrong. Indeed, in its annual ‘Account of the London Hospitals and Schools of Medicine’ in 1836, it claimed that Liston ‘has for some time been renowned as the first operator among British surgeons’ and that ‘[i]f the justly-distinguished, and far-famed ASTLEY COOPER is ever to have a successor, in this metropolis, Mr. LISTON will be that man’.[6] Thus, while in 1824 Liston’s operative style had been derided as ‘ludicrous and anti-surgical’ and actively contrasted with Cooper’s, by the mid-1830s it was presented as its rightful inheritor.

What is remarkable about The Lancet’s volte-face with regards to Liston is the fact that the very qualities of boldness and operative dexterity which had initially rendered him problematic, now functioned as the grounds on which his fame and reputation were most vigorously defended. For example, in November 1836 The Lancet reported on the case of Mary Ann Griffiths, a 20-year-old woman suffering from a horribly disfiguring tumour of the superior maxillary bone. It described Liston’s excision of the bone and its tumour, which took only seven minutes and twenty seconds, as ‘one of the most splendid triumphs that operative surgery has ever achieved’.[7]

Meanwhile, within the very same month, it reported on another similar, though more tragic, case of a 24-year-old shoemaker, known simply as ‘W. B.’, whose face had been injured by a blow from a cricket ball and who had likewise developed a tumour of the superior maxilla bone. In this instance the patient died several hours after the operation. Rather than criticising Liston, however, The Lancet claimed that the operation furnished a ‘valuable lesson’ about the dangers of poorly-trained surgeons, arguing that:

The public … on discovering that an operation may occasionally be followed by fatal consequences even when it is performed by the most distinguished of our surgeons, will shrink in dismay from the thought of entrusting their lives … to half-instructed bunglers, who, under the system of nepotism, obtain the office of surgeon in our old endowed hospitals.[8]

Here, then, The Lancet sought to use Liston’s failure to further illuminate his reputation and castigate the shortcomings of others. Needless to say, such rhetorical contortions were not lost on Wakley’s opponents. The moderate reforming journal, the Medico-Chirurgical Review, claimed that ‘a more bungling attempt to protect a friend could scarce be made’. Questioning the wisdom of Liston’s actions in both cases, it maintained that ‘The day indeed for flashy operations is gone by. The refinement of our manners is disgusted at the exhibition of what wears more the aspect of clever butchery than science’.[9]

Liston’s reputation was, then, determined to a very significant degree by the surgical politics of the metropolis. Indeed, Wakley’s implacable conservative opponent, the London Medical Gazette, thought that it detected more than a little favouritism in The Lancet’s reporting of Liston. Contrasting Liston’s hallowed status with that of William Lawrence (1783-1867), the former radical surgeon and Lancet contributor, turned conservative ‘placeman’, it wrote:

Mr Liston, the present idol of Wakley’s attachment is, we believe, the only person of any standing in the profession in London, who is desirous of the good opinion of the honourable member for Finsbury [Wakley was MP for Finsbury from 1835]; he has not been ashamed to be present at, and to take part in, meetings where Wakley has been prominent: hence, naturally, the reciprocal feeling on the part of the latter. The great attraction now at the North London Hospital is Mr Liston … Mr Liston is held up as the model of surgeons – the greatest after Sir Astley Cooper, and so forth. How is this, when we have Mr Lawrence still amongst us in all his pristine vigour and ability … But Mr Lawrence shook off the patronage of Wakley, and hence the rival that has been set beside his throne.[10]

The case of Robert Liston clearly demonstrates that Romantic surgical identities were shaped not simply by words and deeds, but also by the politics of representation. Likewise, it suggests that issues such as manual skill and operative dexterity, as well as compassion and humanity, could be used to both sustain and undermine surgical reputations. Indeed, what is perhaps most evident from Robert Liston’s fame (and infamy) is that Romantic surgical identities were dependent on a delicate balance between physicality and sensibility, action and judgement.

[1] Cumbrian Archives Service, Carlisle (CAS-C), D HUD 17/90/(uncatalogued), Andrew Whelpdale to John de Whelpdale, 1 January 1833.

[2] James Syme, ‘Successful Case of Amputation at the Hip-Joint’, Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal 21 (January 1824), 19-27 (p. 27).

[3] The Lancet 1:22 (29 February 1824), p. 291.

[4] The Lancet 1:22 (29 February 1824), pp. 291-3.

[5] The Lancet 13: 334 (23 January 1830), pp. 364-5.

[6] The Lancet 27:682 (24 September 1836) p. 20.

[7] The Lancet 27:688 (5 November 1836), pp. 236-40.

[8] The Lancet 27:691 (26 November 1837), p. 344.

[9] Medico-Chirurgical Review 26:51, new series (1 January 1837), p. 276.

[10] London Medical Gazette 19:461 (1 October 1836), p. 25.