Emotions have featured prominently in my research on the impact of disability on injured servicemen’s intimate relationships and family lives.

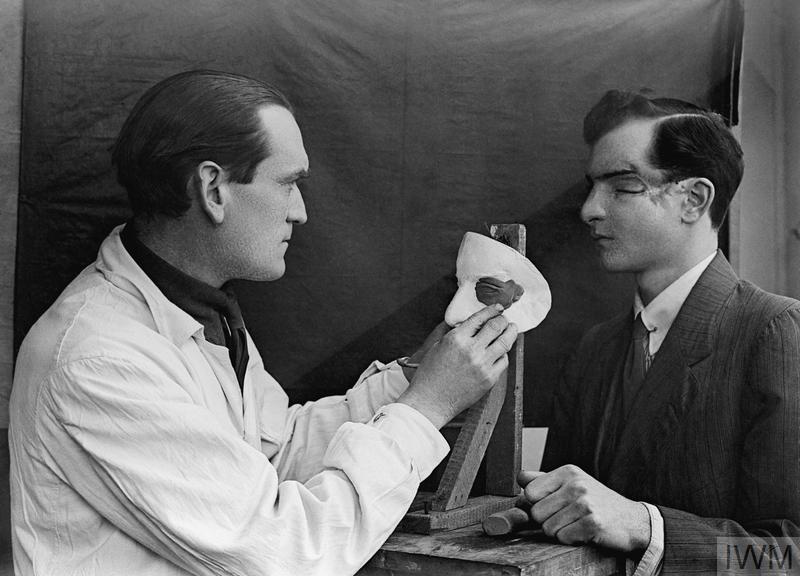

I focus on Second World War veterans’ experiences of facial disfigurement and amputations. Analysing private papers, memoirs, interview transcripts and even being lucky enough to interview some myself, I have followed each injured serviceman from the battlefield to hospitalisation, rehabilitation and finally civilian life. As I begin to write the final chapter of my thesis I have been struck by how much injured servicemen’s emotions towards themselves concerning their masculinity and sexuality changed, particularly in the early stages of their injury and surgical treatment.

Thomas Graham was a driver and wireless operator with the 61st Regiment, Reconnaissance Corps in 1944. During the advance on Belgium Thomas was in a Bren Gun Carrier near the Albert Canal when the driver was shot dead and he was shot in the face. In his memoir he wrote,

I notice a lot of blood and some bits of flesh on my chest…Millions of thoughts flash through my brain…I must have been hit somewhere in the face!!!! My goodness!!!! My mind was racing twenty to the dozen…What happens now? What should I do? Am I dying? Will I die? Millions of thoughts rushed through my mind.[1]

Thomas’s thoughts and feelings, particularly those of uncertainty and death, sum up many of those felt by other servicemen wounded in battle. Uncertainty is a prominent emotion in the post-surgery accounts of servicemen who now faced life with facial disfigurement or amputations. It is likely these feelings of uncertainty stemmed from fears over their ability to fulfill the ideals of domestic masculinity such as getting married, having children and becoming economically independent. The enduring ideals of domestic masculinity, particularly economic independence, were used by the government and general public as markers of success for disabled servicemen.[2] Once he achieved these ideals he was seen to have overcome his disability.[3]

Frederick Cottam served in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment in Belgium when he was severely wounded by mortar fire in 1940. Frederick was only nineteen years old when both his legs were amputated above the knee. His height decreased from 5ft 10 inches to 3ft 6 inches. Reflecting on his hospitalisation he wrote,

Reflecting on a vague future I became despondent. Would I be physically dependent upon others for my care and attention? My fears were not groundless. Even if fitted with artificial limbs, total independence would be unattainable due to my high-up amputations…There was also the problem of work, which would be necessary to live properly. The war pension of even a severely disabled ex-private soldier was pitifully small…Uncertainty breeds fear…This growing feeling of inadequacy began at Ashurst as my general health improved.[4]

Although the surgery saved his life from blood loss and infection Frederick felt inadequate as he thought he might struggle to live independently and find work to provide for himself and any future family. Frederick was young and working-class, with no higher education, additional factors that contributed to his worries about finding suitable employment.

Leslie Beck was a platoon leader in the Wiltshire Regiment in Anzio when he was injured by a shell blast in 1944 resulting in both his legs being amputated. Leslie worried about his sexual future. He wrote in his memoir,

Before the army I was only just beginning to feel the confidence to come to grips, metaphorically speaking, with the company of the opposite sex: with the loss of my legs came a feeling of inadequacy.[5]

As someone who already felt inexperienced with women, the loss of Leslie's legs only added to his lack of confidence and feelings of ‘inadequacy’.

Dennis Neale was part of a secret squadron and was only twenty-three when he was injured during a night mission patrolling the English Channel. His face was completely crushed by the aircraft propeller. When out in public Dennis experienced people whispering and staring at him, but how Dennis saw himself was just as important as the public’s reactions. He said in an interview with Liz Byrski,

It took some time for that to sink in because even when you know there are no more operations and you look in the mirror, you’re still not seeing the man you were. There’s someone else there, and he’s nothing like as good looking as you. I kept wanting to get myself back, and hoping to see what I remembered instead of what was really in front of me…You get used to it or you don’t and I know some of the fellows didn’t. I’ve got used to it.[6]

Despite reconstruction Dennis could not change the alienation he felt from his pre-war self. As a formerly handsome RAF pilot, he could not emotionally equate his new face with the man he used to be. His identity had been profoundly challenged by his injuries and surgeries.

In this short blog post I have highlighted the uncertainty felt by servicemen towards fulfilling contemporary masculine and sexual norms after surgery and subsequent disability. Contemporary popular culture and current public memory regarding the experiences of war veterans who have experienced life changing injuries and surgeries in the past and present tends focus on the narrative of overcoming adversity in the form of disability. The idea that disability is something to be overcome or conquered has negative connotations and automatically judges those people living with disabilities by ableist standards rendering those who do not meet these standards as failures. Furthermore the ‘overcoming’ rhetoric actually distracts from wider issues facing those with disabilities, such as accessibility in public transport and places, higher education and the workplace. I believe more research in these areas that consults the lived experiences of people living with disabilities would help a great deal to bridge these gaps in society.

Jasmine Wood is final year PhD candidate based at the University of Strathclyde. She is currently researching ‘Disability and intimacy in the lives of British soldiers wounded in the Second World War'. Her research examines the impact of disability on the intimate and familial relationships of British veterans disabled by amputations, facial wounds and burns. It explores the place of sexuality in rehabilitation programmes and popular representations of disabled British servicemen. Veterans’ personal experiences are used to explore the validity of these representations and how men coped with their impairments. Through an exploration of these themes, this project helps to address the contemporary issue of stigmatisation surrounding discussions on sexuality and disability.

[1] T. Graham, Private Papers, Imperial War Museum Archive, Documents.25844, p. 9-10.

[2] J. Anderson, ‘Turned into Taxpayers: Paraplegia, Rehabilitation and Sport at Stoke Mandeville, 1944-56’, Journal of Contemporary History, 38:3 (2003).

[3] Back to Normal (1944), (Produced by Ministry of Pensions and Ministry of Information), Medical Services & Warfare Online Archive.

[4] F. T. Cottam, Private Papers, Imperial War Museum Archive, Documents.18942, p. 101-102.

[5] L. C. Beck, Private Papers, Imperial War Museum Archive, Documents. 19013, p. 11.

[6] L. Byrski, In Love and War: Nursing Heroes (Australia: Fremantle Press, 2015), p. 94.